Selling Snipcart: Part One

The last 7 months have been f*cking crazy. I worked, learned, argued, dreamt, and stressed more than I usually do. Why? We sold Snipcart.

→ TechCrunch post

→ Part One

→ Part Two

→ Part Three

The story that follows is told from my perspective. Everyone mentioned in this post has read and approved it.

The last 7 months have been f*cking crazy.

I worked, learned, argued, dreamt, and stressed more than I usually do.

Why?

We sold Snipcart.

That's right; your friendly neighborhood nerds sold their indie, developer favorite e-commerce platform.

I'm pretty sure my NDA forbids me to expose too many details. Still, I can share enough for this to be a great story.

rewind to Summer 2020

The Covid boom is still, well, booming for us at Snipcart.

Yet another platform approaches us to add our e-commerce functionality into their product. My boring answer:

"Sure thing! Have at it. We'll help with support but can't do much else. Our small team is already stretched thin."

And the classic:

"Sorry, no, we won't be developing XYZ features."

The call ends. I'll probably never hear from them again, I think to myself. Oh well, back to work, there's a sh*t ton to do.

A couple of weeks pass. They follow up:

"Our CEO would like to speak with you about this partnership."

Sigh. Support tickets are soaring. I'm desperately searching for a lead marketer to replace my friend Math, who's moving on. We're onboarding new team members. Merchants are gearing up for the holidays. I ain't got time for that.

"I'm sorry, I can't. I'll be available next year to chat. Things are hectic here."

A month passes. The CEO follows up himself:

"Hey, can we discuss this next week? I'd like this matter to move quickly."

My rebel teenager ego awakens. WTF is "this matter," and who is this guy? I ain't got time for that!

"I'm sorry, I can't. I'll be available next year to chat like I told your colleague. Things are hectic here."

All right, moving on.

FFWD, New Year comes along.

The team slowly emerges from the most boring holidays of the century. Back to work. Yearly goals, hiring plans, ambitious roadmap, LET'S GO.

Mid-January. We withdraw extra dividends for partners for the first time in 8 years. My girlfriend and I jump from joy in our apartment—kind of a next best thing lockdown victory lap.

The week after that, the CTO (CEO cc'd) follows up. I'm like, f*ck me these folks don't give up easily.

"Sure, let's talk."

We chat for an hour. I try my best to explain why Snipcart isn't purely a headless player. My ramblings clash with their initial mental model. The CEO, on vacation with family, leaves halfway through the call. I offer to send over a video and some more documentation. Bye-bye.

NOW I won't hear from them again, I conclude.

The follow-up email pops up in my inbox the very next week. They have consulted the material, as well as one of my articles, and made a proof of concept integration. I respect the effort, so I agree to another call. I bring my partner Charles along for the technical details.

The integration is tight, and so is their understanding of Snipcart vs. their product. We're legit impressed. They ask for white labeling and deeper integration. We fumble half-truths about it being "possible yet slightly complex" or whatever. Some polite excuses (we're Canadians) about not having the time to help them with that.

Now for the curveball.

"Listen, guys; we'd really prefer owning that technology. Would you be open to an M&A?"

I have no clue what that means.

Tiny panic attack. My mechanical keyboard will be too loud if I Google it on the spot. If I mute right now, it'll just look weird. F*ck!

I pull out my best baritone CEO voice and, with shallow confidence:

"Hmm, just so we're all on the same page here: what exactly do you mean by EMENAE?"

"Merger & acquisition."

Holy moly, these folks want to buy us?

I tell them we're not for sale unless they have a crazy amount in mind. I remind them that Snipcart is a growing, profitable business with revenue records in 2020. That all of our metrics are pointing up. Oh, and also: we freaking love growing it.

"I don't mean to be rude, but do you have the budget to purchase such a company?"

The jab lands. We get inundated by their growth metrics.

- >17k paying customers

- >1M live sites

- >200 employees

- Series D about to close

Other numbers I can't share, but they're much higher than ours — duh.

"Woah, impressive! I'm happy for you."

They tell us the acquisition could involve a significant cash component. Snipcart could remain an independent entity, but they would be our "priority partner." We could grow a team in Canada, etc.

The time:info ratio is dizzying. We agree to pause this call and let Charles and I talk it over with partners.

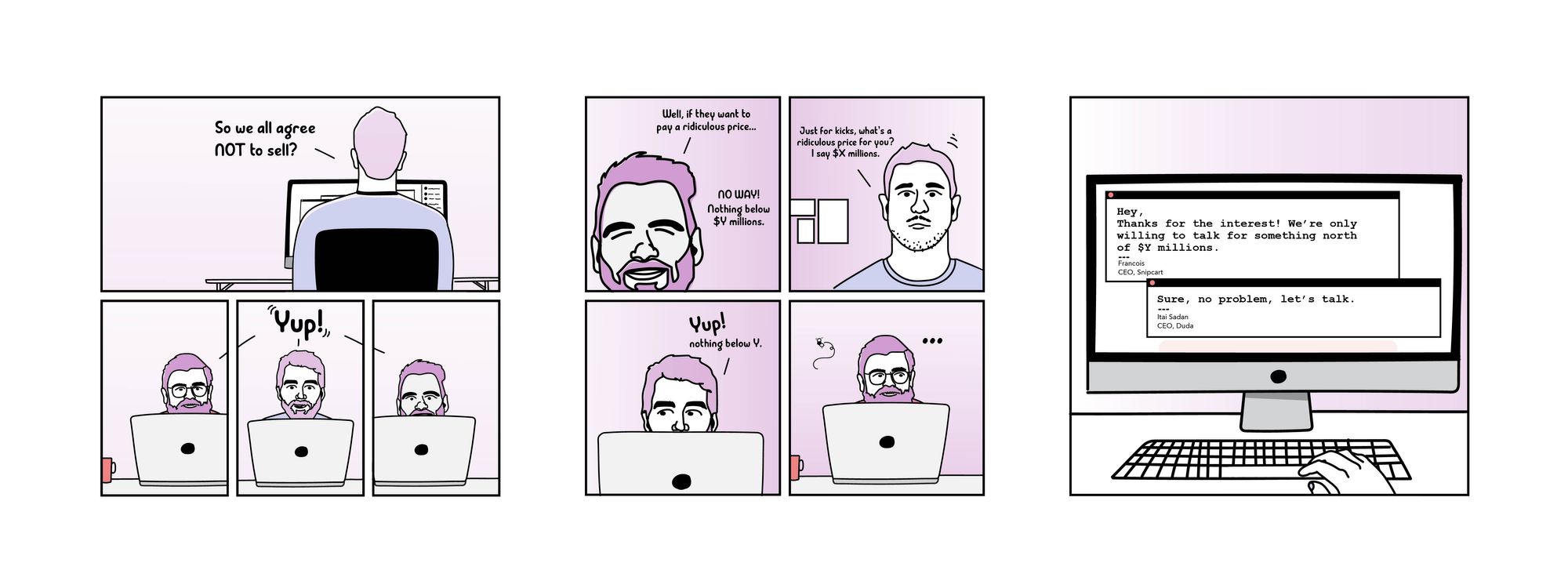

The four of us — Georges, Vincent, Charles, and I — did just that. Our conclusion? Not selling.

We loved Snipcart. We were proud of what we've built. Things were going well. Lifestyle, profitability, traction, etc. Why mess with that good a thing?

Still, it was an unexpected opportunity to ask ourselves: what would make us consider selling? It boiled down to two things:

- A very significant cultural and technical fit — leading to a net positive for our team's careers.

- A very significant amount of money — capturing all of the value and efforts we've put in.

We argued for a week over what that amount should be. The initial absence of desire to sell settled it: we'd go with the highest of the numbers thrown around.

I wrote back to the CEO, stating we would only be interested in talking above X.

The four of us thought that would be the end of it. Couldn't have been more wrong. 😂

Imposter syndrome

You're often better than you think. This realization happens now and then. Friends reminding you of your accomplishments, winning prizes, that kind of stuff. Or therapists — they're good at that.

Something of the sort happened during the deal. At first, I thought Duda were only interested in buying our technology at the lowest price possible. I thought they'd try to lowball us, take the tech stack, get rid of "non-essential" employees, etc.

Soon, however, I realized I was mistaken. They had a big multiple in mind for valuation, and they were adamant about keeping the whole team on board. For some, this seems like a given; it wouldn't make sense to acquire a product without its architects. To me, it wasn't obvious. I had never sold a company, nor had I been exposed to friends who had. In the absence of empirical data, my mind defaulted to fear and mistrust. I do expect the worst most times. It's something I'm working on.

This event, however, was a motivating boon for my ego. Again, it might sound obvious, but when someone says they're willing to pay millions of dollars for the company you've built, it becomes hard to ignore how valuable and awesome your work is.

So take that, I guess, impostor syndrome. 😊

Validating seriousness

First, we tried to validate how serious the buyer was. In parallel, I started learning about buying and selling businesses. I listened to The Art of Selling Your Business on Audible. Talked with experienced entrepreneurs; partners did the same. Took notes. Most early advice led to the same step: get an official LOI (Letter of Intent) ASAP. We insisted politely and eventually got one. FYI, an LOI isn't really legally binding. It's two parties agreeing to explore the possibility of a deal in good faith. You can walk out at any point.

Still, it isn't the type of document you sign blindly — enter the lawyers. An acquaintance of Georges in Montreal's VC industry suggested three different law firms. They all had decent experience with mergers and acquisitions. We hurried them through short interviews and picked the most senior. We figured it wasn't time to cheap out for this type of deal.

Soon, our lawyers informed us the LOI was relatively "thin." Minimal details included. This isn't necessarily problematic. However, it can lead to more confusion, delays, and arguments further down the road. Take retrading as an extreme example. It can happen when buyers deliberately stretch or intensify the due diligence period (the months where buyers verify product, team, finances, legal, etc.). Doing so stresses and distracts the founders, who pay less attention to operations. Over many months, maybe the business numbers start dropping. Once that happens, buyers then ask for a discounted purchase price, effectively engaging in "retrading." Nightmarish stuff.

Being naturally anxious, I wanted to protect Snipcart from anything of the sort. So did my partners. Beefing up the LOI, while costly in early legal fees, helped shelter our operations and outcomes. Lots of items usually reserved for the SPA (Share Purchase Agreement, the final "deal"), we determined straight into the LOI, like:

- Due diligence max. length

- Precise terms for:

- Cash

- Stocks

- Bonus

- Vesting

Validating technical fit

So validating how serious the buyer came first. Second? Technical and cultural fit.

After a couple of exchanges between teams, we knew where we stood. Both sides had mature tech stacks and knew what would need refactoring, new features, or both. The integration would come with some challenges, but nothing excessive. Charles and I were excited at the thought.

It would accelerate the development of some key features we had wanted to ship for a long time. It would also put Snipcart into the hands of many, many more users. We'd get to scale our systems to handle transaction volumes orders of magnitude higher than our current ones.

Product people will understand how thrilling such challenges are, especially bootstrapped folks. Of course, we honor the slow pace and embrace ruthless prioritization. We have to let our minds teem with ideas, most of which will never materialize. It's kind of heartbreaking, but it's the price to pay for building a solid, focused product that can power an independent company.

Scaling Snipcart

This dissonance between Snipcart's potential and actual pace was always bittersweet to me. Especially when I stepped up as CEO. On the one hand, I cherished our independence. On the other hand, I lamented the delta between our position and some visions of the company. These reflections, coupled with our category momentum, drove me to entertain the possibility of raising VC funding — even before this deal was on the table. In 2020, I had interesting discussions with some venture capitalists. Few understood where Snipcart stood. Most were riding late investment thesis waves around "headless e-commerce" and "Jamstack." Our brand and SEO were on point, so they kept coming. I widened my discussion scope to include founders and employees who had ridden the VC hyper-growth train.

Eventually, I concluded it wasn't for our team nor me. The early years after raising funding felt scarily high-pressured. I heard terrible stories about overly involved investors or disconnected, ego-driven board members. Knowing how anxious and authority-adverse I was, I thought it'd burn me (and maybe our company) out.

So, no VC.

A strategic acquisition, however? Somehow that story resonated more with me. Less so with Georges. He's a savvy entrepreneur, so of course, he'd consider various offers. At the same time, though, he's a firm believer in building long-lasting, "indestructible" businesses. And in his capacity to do so—something he's proven with Spektrum Media, their Quebec-based agency that is well into its second decade of success today.

(Snipcart trivia: we incubated inside Spektrum's agency in our beginnings. Details here.)

I chose not to spend my CEO hours chasing potential acquirers. I wasn't even sure if we would want to sell. I figured focusing on product, brand, and the team was a better use of my time. Fast forward a few months, and sure enough, a strategic acquirer showed up at our virtual doorstep. Life's funny like that sometimes.

There was a lot of serendipity involved with this deal. Covid, e-commerce boost, our biggest year ever… all the macro ingredients were in play, making our company an exciting opportunity for bigger players. There were also lots of close calls throughout. Some this story will tell, some I'm simply not comfortable sharing. What I want to make clear is this: luck played its usual role.

In recent years, we had seen interest in buying Snipcart. Three "serious" opportunities that I can recall. Dozens of bland offers to open dialogue. Before that time, however, the company had never reached an optimal running rhythm. Growth varied from year to year. Transactions scale wasn't super impressive. Profits were present yet not significant. Team was a bit small, relying on key individuals instead of scalable processes. You get the idea.

Snipcart in early 2021, though, was at a different place. We had crossed the 1M ARR bar. Scaled team over 10. 120% YoY growth, profits, decent runway. Our visibility was good in the space, brand amplified through word of mouth, more PR, good SEO.

Discoverability and scalability were much, much better. Maybe it boils down to that. And luck, always.

Validating cultural fit

How do you even validate cultural fit?

Number one goal for this part was:

Make sure Snipcart remains an awesome place to work at.

We wanted our values of fun, transparency, proximity, and trust to emerge from this deal intact. We wanted our minimal viable process approach to stay in place. For instance, we never tracked hours at Snipcart. We rely on trust and self-management, with sprint-based and yearly objectives. This is just one example of the many things we didn't want to lose.

Now there is no surefire way to audit something as immaterial as culture. Especially during Covid. So we relied on proxies, asking questions like:

- Can we meet and talk to other teammates?

- How do you measure progress at Duda?

- How long are employees staying on average?

- What are your Glassdoor reviews like?

- What's a typical work week like at Duda?

- How much time do you spend in meetings?

- How involved is the mother base in satellite offices like Brasil?

I also used some connections to get opinions and information about the company. By opening these various threads, we could draft a clearer, appealing portrait of Duda as a company, not just a buyer. We learned that small, self-reliant "squads" composed the global workforce. That each of these squads was free to determine its own goals and work methodologies. We learned that mid to senior individual contributors and managers stayed for 6-8 years. That many employees had young families, which they could take care of through flexible schedules and excellent health benefits. We learned that the dev teams in Israel worked a bit longer hours than us. That meetings were a bit too present, but so was the desire to reduce them.

Most important of all, we learned that Duda celebrated its different offices' particular cultures. There were no strong-handed efforts to uniformize operations across offices. Some light efforts, sure, but nothing too involved. That was super important: we knew most of our team valued our smooth, self-organizing vibe — a lot. We often describe our culture as follows:

We take our work seriously, but ourselves, not so much.

If we were to sell to an organization that takes itself too seriously… the clash would be significant. Fortunately for us, we stumbled upon the one company with its cultural roots steeped into The Big Lebowski. I'm not kidding: "Duda" is a love letter of a brand name to The Dude, His Dudeness, Duder… El Duderino if you're not into the whole brevity thing.

Unless you're the penultimate hypocrite, it's impossible to adore this absurd masterpiece and AND take yourself too seriously. I would eventually meet Itai and Amir in person and validate this hypothesis. But earlier in the deal, this helped them pass the culture test with flying colors.

I was extremely transparent from the get-go. I stated clearly what we were willing to change and what would need to stay in place. They showed lots of openness towards this and offered to respect most if not all of our conditions-related requests. During that phase, I came to appreciate how important our team was to them. It felt good. I was able to quickly negotiate meaningful compensation bumps for everyone, along with stock options. All without pushbacks or friction.

(We're talking about-to-go-public stock options here, not that airy young startup promise we've all heard about.)

These bumps were vital to us. Symbolic. We've always said and known that Snipcart wouldn't have gotten this far without the dedicated team members who shared years of their careers with our startup. And we knew we weren't paying top market rates, especially for devs. People stayed because they had fun, cared for one another and for our company. Regardless of the 15-30% bump, they could've had elsewhere. Just writing this makes me emotional. I'll never thank all of you enough.

It's a wrap for Part One!